SHM Submits Comments on the 2025 Physician Fee Schedule Proposed Rule

September 09, 2024

SHM's Policy Efforts

SHM supports legislation that affects hospital medicine and general healthcare, advocating for hospitalists and the patients they serve.

Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services

Department of Health and Human Services

Attention: CMS-1807-P

P.O. Box 8016

Baltimore, MD 21244-8016

Dear Administrator Brooks-LaSure,

The Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM), representing the nation’s more than 50,000 hospitalists, is pleased to offer our comments on the proposed rule entitled Medicare and Medicaid Programs; CY 2025 Payment Policies under the Physician Fee Schedule and Other Changes to Part B Payment and Coverage Policies; Medicare Shared Savings Program Requirements; Medicare Prescription Drug Inflation Rebate Program; and Medicare Overpayments (CMS-1807-P).

Hospitalists are physicians whose professional focus is the general medical care of hospitalized patients. They provide care to millions of hospitalized Medicare beneficiaries each year. They see firsthand how patients admitted to hospitals today are often sicker and more frail compared to those prior to the COVID-19 pandemic. They are committed to providing high-quality care to patients, often leading clinical quality, systems and operational improvement efforts in the hospital. In addition to managing clinical patient care, hospitalists also work to enhance the performance of their hospitals and health systems. The unique position of hospitalists in the healthcare system affords them a distinctive role in both individual physician level and hospital-level performance measurement programs. It is from these perspectives that we offer our comments on this proposed rule.

I. Comments on the Medicare PFS Conversion Factor

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) estimates the CY 2025 Physician Fee Schedule (PFS) conversion factor to be $32.3562, which is an approximate 2.8 percent cut. The proposed conversion factor is the result of the expiration of a temporary legislative update to the CF for 2024, and a 0 percent update for 2025 under the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act. The American Medical Association (AMA) estimates the

conversion factor reduction will amount to an approximate 2.4 percent cut to hospitalists’ Medicare reimbursements.

SHM continues to raise our concern over repeated, consistent cuts to the Medicare PFS. These cuts exacerbate on-going staffing and clinician coverage issues across the healthcare system. According to respondents of the 2023 State of Hospital Medicine Report, nearly 80 percent of hospital medicine groups reported unfilled positions. On average, approximately 10 percent of their budgeted FTE positions remain unfilled, and added financial pressures through continued cuts in the MPFS will continue to intensify this dynamic. Staffing shortfalls are contributing to clinician burnout and will continue to impact the quality, safety, and efficiency of patient care in the hospital setting.

SHM has endorsed several pieces of legislation to address different aspects of this issue. The Strengthening Medicare for Patients and Providers Act (H.R. 2474) would create a permanent inflation-based update tied to the Medicare Economic Index (MEI). Both MedPAC and the Medicare Trustees have warned about the dangers of repeated Medicare cuts. Continued cuts pose a threat to care access and quality. Physicians are one of the only Medicare provider groups without an inflationary update and according to the AMA, inflationary pressures have resulted in an approximate 26% decrease in physician payment when adjusted for inflation since 2001.

SHM also supports the Provider Reimbursement Stability Act (H.R. 6371), which would provide much needed reforms to the budget neutrality threshold under the PFS. The current threshold was established in 1992 and has never been updated to better support our rapidly changing healthcare landscape. Raising the budget-neutrality threshold would allow for greater flexibility in determining pricing adjustments for services without triggering repetitive across-the-board payment cuts.

SHM is deeply concerned that continued cuts in the PFS, combined with the pressures of inflation, are creating a financial crisis in the healthcare system, causing patient care to suffer as a result. CMS must continue to explore how to redress this critical issue, which includes working alongside Congress to create a more stable payment system.

II. Payment for Medicate Telehealth Services under Section 1834(m) of the Act Frequency Limitations on Medicare Telehealth Subsequent Care Services in Inpatient and Nursing Facility Settings, and Critical Care Consultations

CMS has proposed to remove the existing telehealth frequency limitations for the Subsequent Inpatient Visit CPT codes (99231-99233), Subsequent Nursing Facility Visit CPT codes (99307-99310), and the Critical Care Consultation Services (G0508, G0509) for CY 2025, which is an additional year extension. These code sets have limitations of once every three days, once every fourteen days, and once per day, respectively. The frequency restrictions were temporarily removed during the COVID-19 PHE.

SHM supports the extended removal of frequency limitations for subsequent hospital visits and encourages CMS to consider removing them permanently. Hospitalists’ experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic demonstrated how telehealth technology, and patients’ readiness to embrace it, has evolved dramatically since these codes were first adopted into the Medicare Telehealth Services List. Arbitrary limitations on how frequently these codes can be billed (once every three days) are not based on patient care needs. They serve as an impediment to care and create an unnecessary requirement to track code usage in order to accurately bill for patient care. Frequency determinations should be based on medical necessity or the needs of individual patients, with guardrails established by the provision of further detailed guidance and the establishment of clear definitions of what is appropriate and reasonable.

III. Valuation of Specific Codes

Hospital Inpatient or Observation (I/O) Evaluation and Management (E/M) Add-On for Infectious Diseases

CMS proposes to implement a new HCPCS code to describe intensity and complexity to hospital-level care associated with infectious diseases. The new code, GIDXX, would be available to report for clinicians with infectious disease training and will account for work such as disease transmission risk assessment and mitigation, public health investigation, analysis and testing, and complex antimicrobial therapy counseling and treatment.

Hospitalists often work hand-in-hand with Infectious Disease teams in hospitals, developing and implementing care plans for patients who are hospitalized with or develop infections. This new HCPCS code will serve to recognize the depth of work and time required for managing patients with infectious diseases in the hospital setting. SHM is fully supportive of this proposal for the add-on code.

IV. Enhanced Care Management

Strategies for Improving Global Surgery Payment Accuracy

CMS is proposing to broaden the applicability of transfer of care modifiers for 90-day global services to more accurately deliver reimbursement by breaking down payments into preoperative management, surgical care only, and postoperative management only. CMS is also proposing a new add-on code for postoperative care services. The intent of this add-on is to more appropriately compensate for this care when it is rendered by a practitioner who was not involved with performing the surgical procedure.

SHM appreciates CMS’ efforts to ensure global payment periods accurately reflect the delivery of services during the respective payment period. Much has changed and continues to change in the management of surgical and immediate post-operative patients, including the continued expansion of co-management of patients between hospitalists and specialty service lines in the hospital. We support efforts to ensure clinicians who provide care, both surgical and non-surgical, are being paid for the services they deliver.

V. Updates to the Quality Payment Program

SHM appreciates the opportunity to comment on specific proposals and requests for information for the Quality Payment Program under the PFS.

Request for Information on MIPS Value Pathway (MVP) Adoption and Subgroup Participation

CMS asks for feedback on continuing to transition away from traditional MIPS reporting into MIPS Value Pathways (MVPs) and on subgroup reporting in MVPs. CMS stated it believes it may be able to move entirely to MVPs, potentially as early as CY 2029. Furthermore, CMS intends to require subgroup reporting from MVP participants, which would require multispecialty groups to report on MVPs for their different represented specialties.

SHM estimates more than 50,000 hospitalists practice in hospitals today, which accounts for roughly 5% of the total number of practicing physicians in the country. If CMS used these numbers to determine our specialty, hospitalists would be one of the top 5 largest physician specialties. The only groups larger are Internal Medicine, Family Medicine and Pediatrics (all three of which currently have hospitalists in their counted ranks). Given the size of the specialty and its integral role in caring for hospitalized patients, we continue to be concerned that current MVP structures and policies are not relevant to the practice of hospital medicine. MVPs, as currently set up, do nothing to address the challenges hospitalists face in deriving useful and actionable data from MIPS participation.

SHM continues to oppose the rapid adoption of MVP reporting, particularly because there are no available MVPs for hospitalists. Furthermore, the pathway to develop a relevant MVP for hospitalists is uncertain and quite possibly unattainable. CMS estimates 80% of specialties will have an MVP in 2025 if their newly proposed MVPs are finalized. We disagree with the interpretation of this data. The existence of a MVP for a specialty does not guarantee the MVP will be relevant or of any utility to the work of the clinicians in that specialty. For example, many hospitalists are identified in CMS data as Internal Medicine or Family Medicine. However, they would not be able to report MVPs designed for outpatient primary care work, regardless of CMS’ classification.

CMS should not eliminate traditional MIPS reporting until all MIPS eligible clinicians are able to utilize meaningful and actionable MVPs. This should be the determining factor of sunsetting the MIPS. We do not view CMS’ potential option of a “global MVP with broadly applicable measures” as an alternative for clinicians who do not have an MVP. One-size-fits-all approaches to quality measurement and performance assessment disengage clinicians from the program and will predictably lead to unnecessary administrative burdens.

SHM continues to oppose mandatory subgroup reporting and urges CMS to further examine the administrative burden associated with this policy. There is limited evidence that MIPS has had any positive impact on actual patient care. We believe the added administrative burden of mandatory subgroup reporting outweighs the hypothetical benefits at this time. Furthermore, until CMS has an inventory of meaningful, actionable MVPs for all specialties, it is premature to anticipate requiring subgroup reporting.

We appreciate CMS exploring some of the challenges with subgroup reporting, such as defining specialties for the purpose of subgroups. As we have commented in prior rulemaking cycles, hospitalist groups are frequently considered “multispecialty” when using Medicare claims and PECOS identifiers. A typical group of hospitalists can include Internal Medicine physicians, Family Medicine physicians, Hospitalist physicians, nurse practitioners, and physician assistants. Using a TIN to help determine subgroups (i.e., allowing a multispecialty TIN to identify as a “single specialty group”) would not solve this operational challenge. Groups do not assemble TINs for the purpose of or with the expectation that it will be meaningful for MIPS reporting. It is therefore an inappropriate tool to determine appropriate subgroupings.

CMS also explored potential limits on subgroup composition to avoid recreating multispecialty groups where a portion of the clinicians are not reporting on quality measures. We strongly urge CMS to do more research in this area, particularly around the size and composition of groups, before establishing limits.

Data Completeness Criteria for the Quality Performance Category

CMS proposes to maintain the data completeness threshold for quality measures at 75% through the CY 2028 performance period/ 2030 MIPS payment year, which is an additional two years. SHM strongly supports maintaining the data completeness threshold. We continue to urge CMS to examine challenges for clinician data aggregation, particularly when practice sites use different EHR systems. Some sites may struggle to aggregate data because EHR systems allow for customization, meaning the data may not be collected in a consistent manner across sites, even within the same EHR system. Different versions of EHR systems may also impede complete data collection. We believe the current threshold still provides an acceptable snapshot of a group or an individual’s performance on a measure, while maintaining flexibility for operational and implementation challenges participants may face.

Guiding Principles for Patient-Reported Outcome Measures in Federal Models, and Quality Reporting and Payment Programs Request for Information

SHM appreciates the opportunity to provide comments on expanding the portfolio of patient reported outcome measures (PROMs) in federal programs. We believe patient voice and experience is an integral component of a high-quality, efficient healthcare system and laud CMS’ efforts to increase opportunities for patient input.

CMS discussed a set of guiding principles and considerations they could use to help the agency select and implement PROMs, including data infrastructure, measure testing, feasible clinical implementation, accessible, patient engagement, and equity. We encourage CMS to expand its list of potential guiding principles to add concepts relating to clinician engagement and meaning. One common challenge with quality measures is they are not consistently created to drive clinician actionability and relevance. We believe it is important to create measures that are both meaningful to patients and clinicians and provide data that clinicians can use to improve their practice of medicine. However, there can be discrepancies between what clinicians consider a valid and meaningful measure of their practice and what patients prioritize and value. We encourage CMS to prioritize measures that meet both aims. CMS should also explore potential unintended consequences for each PROM under consideration, particularly if it is considering using measures in pay for performance programs.

Attribution is also a critical component for any measure construction. Existing measures typically try to attribute performance to a single clinician. In the hospital, numerous clinicians care for patients. Patient handoffs, in which one hospitalist hands off care of a patient to another hospitalist, are common. Therefore, attribution to a single clinician may not accurately portray the reality of patient care. CMS should include consideration for how a measure is attributed to clinicians and their ability to affect performance on the measure.

Cost Category: Proposed Respiratory Infection Hospitalization Episode Based Cost Measure

CMS proposes to implement a Respiratory Infection Hospitalization episode-based cost measure in the cost category of the MIPS. This measure is a revision of the previously removed Simple Pneumonia with Hospitalization episode-based cost measure. We are opposed to implementation of this measure in the MIPS, primarily due to longstanding issues with attribution and actionability of these episode-based cost measures. We believe this Respiratory Infection Hospitalization episode-based cost measure may be more appropriate at a systems-level, and SHM could be supportive of the measure outside of the MIPS construct.

SHM continues to have concerns about episode-based cost measures, particularly around attribution to clinicians or groups. These measures contain services and care that span across settings and providers. For example, the Respiratory Infection Hospitalization measure includes services that occur within thirty days of the trigger event. Hospitalists, who are highly likely to be attributed cases in this measure, do not typically have control over costs outside of the hospital, and certainly not for thirty days post the triggering event. Furthermore, costs in the hospital are largely fixed by the DRG associated with the hospital stay, limiting their ability to impact costs in this measure. While the structure of the measure may be relevant to CMS, it has limited actionable relevance to front-line clinicians. We do not believe it is appropriate to adjust reimbursement rates based on measures where the attributed clinician has limited, to no, ability to impact performance.

We urge CMS to rethink their approach to cost measures more generally for the MIPS, given the program is meant to assess performance and adjust payments for individual clinicians and groups. Measures in this program must be clinically relevant to who is being measured/attributed cases, and there has to be reasonable opportunity for improvement. The episode-based cost measures typically attributed to hospitalists all suffer from the same issue - lack of ability for hospitalists to affect the costs in the measure. CMS must prioritize meaning and actionability for the attributed clinicians when developing measures. To do otherwise serves to increase apathy among clinicians and ultimately creates mistrust in these programs.

Improvement Activity Scoring and Reporting Policies

CMS proposes significant changes to the scoring and reporting policies for the Improvement Activity category of the MIPS. Currently, a clinician or group reporting traditional MIPS must report on 40 points worth of activities. These activities are weighted by some combination of high- (20 points) and medium- (10 points) for purposes of scoring. The proposed changes include removing the weighting of activities and require the reporting of only two activities. In addition, MVP participants would only report on one activity.

SHM strongly supports the proposed simplification of the Improvement Activity category by removing activity weights and requiring only two activities be completed in order to obtain full credit in traditional MIPS. We have long believed improvement activities constitute valuable operational and quality improvement efforts that are otherwise not captured by the MIPS. By simplifying the reporting on this category, MIPS participants will have a consistent goal for this category and will now be able to select activities that are of the highest value to their patients and practices.

Scoring for Topped Out Measures in Specialty Measure Sets with Limited Measure Choice

CMS proposes a change to their topped-out measure policy to address limited measure choice and scoring opportunities in the MIPS. The existing topped-out methodology caps performance on topped out measures at 7 out of 10 points, immediately disadvantaging clinicians and groups that have no other measures to report. We commend CMS for acknowledging this challenge, along with recognizing anemic measure development as they propose an alternative topped out scoring methodology.

Specifically, CMS proposes to apply a defined measure benchmark with scores up to 10 points for selected topped out measures. This would enable clinicians or groups to still score the full 10 points on a measure if they achieve 100 percent performance. SHM supports this proposed change to the topped-out measures scoring and benchmarking methodologies to ensure clinicians and groups are not disadvantaged by a dearth of measures to report. Furthermore, we urge CMS to expand the available measures for this benchmarking to ensure that hospitalists are not left behind.

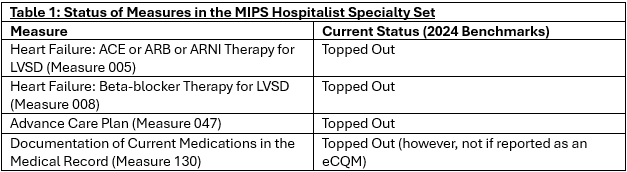

CMS proposed a list of sixteen measures that would be eligible for this topped-out benchmarking methodology. The MIPS hospitalist specialty set has four measures to report (Table 1). All four measures are topped out in some capacity. Notably, none of the measures on the hospitalist specialty set are included in the proposed topped out benchmarking.

Unless CMS expands the measures included in its proposal, hospitalists who report in traditional MIPS are limited to a maximum of 28 out of 40 points available from these quality measures. This is a structural disadvantage in overall MIPS scoring. CMS must address this scoring disadvantage in their final rule. As stated previously, SHM estimates more than 50,000 hospitalists practice in hospitals today, which accounts for roughly 5% of the total number of practicing physicians in the country. To avoid disadvantaging a MIPS cohort of this magnitude, we strongly urge CMS to include all of the measures in the MIPS Hospitalist Specialty Set in their published list of measures available for the topped-out benchmarking.

It is our understanding that at least some of the measures in the hospitalist specialty set (Measures 47 and 130) were not included in the proposed measures for the topped-out benchmarking because they are cross-cutting measures included in a large number of specialty sets. The concern is that clinicians might elect to report on some of these topped out measures even if they have other measures available in their specialty sets to try to optimize their scoring in the program. We believe these fears are unfounded and could potentially be prevented by CMS using existing processes.

CMS has an existing policy to reduce the denominator of the quality category when a clinician or group reports on fewer than the required six measures. The Eligible Measure Applicability (EMA) checks whether there were other measures a clinician could have reported and did not. CMS could leverage the EMA to ensure clinicians or groups who report on topped out measures, including those like Documentation of Current Medications in the Medical Record, could not have reported on measures that were not topped out. This would enable CMS to expand the list of measures available for the topped-out methodology, while still meeting its program integrity goals.

Establishing the Performance Threshold for the CY 2025 Performance Period/2027 MIPS Payment Year

CMS proposes to continue using the mean total performance score from the CY 2017 performance period/2019 MIPS payment year. This would keep the overall MIPS performance threshold at 75 points. SHM supports this proposal. We appreciate CMS’ acknowledgement of the continued staffing and operational challenges in the health care system, and the relative unfamiliarity of cost measures and scoring in the cost category.

Conclusion

SHM appreciates the opportunity to provide input and comments on the 2025 Physician Fee Schedule proposed rule. If you have any questions or require additional information, please contact Josh Boswell, Chief Legal Officer/Director of Government Relations at jboswell@hospitalmedicine.org or 267-702-2635.

Sincerely,

Flora Kisuule, MD, MPH, SFHM

President

Society of Hospital Medicine